Parameters

One of the most rewarding aspects of creating a procedural generation system is exploring what it can make. The initial investment of time spent coding is repaid by the ability to iterate easily and quickly. Many procedural systems can produce endless variations and can be pushed to surprising extremes. Exploring the range of the system reveals new ideas to consider and aesthetics to explore.

Procedural generators can provide enormous creative leverage. They allow expressive artistic control while automating much of the work. This control is afforded by exposing parameters. Parameters are adjustable values that influence the internal behavior of a system.

Parameter Space

A parameter space is the set of all possible combinations of values for the parameters of a system. The parameter space of a system can grow very quickly. A system with one boolean parameter can be configured in just two ways. If the system has 8 boolean parameters, it can be configured in 256 ways. A system with 16 boolean parameters will have 65,536 combinations. This rapid growth is referred to as combinatorial explosion.

When changes to input parameters map to interesting changes in output, combinatorial explosion can make a procedural system very powerful. Consider a program that generates faces by choosing from 4 options for each of these traits: hairstyle, hair color, eye color, eye shape, nose shape, mouth shape, ear shape, and face shape. Such a system can generate 4^8 or 65,536 distinct faces. If the system supported two more similar traits, that number of outputs would grow to 1,048,576!

Sameyness

Leveraging combinatorial explosion in your procedural system does not guarantee variety.

Sometimes different parameters will lead to the same final output. Sometimes the output will differ only slightly or in ways that are not meaningful or important. When this happens a system’s output can feel monotonous, uninteresting, and “samey”. A system that takes just two numeric parameters (as 32-bit floats) has a little less than 18,446,744,073,709,551,616 (18.4 Quintillion!) states. This is an inconceivably large number, but it is quite likely that many of those states would look very similar. The p5.js ellipse() function takes four parameters: x, y, width, and height. These are each 64-bit floats, so there are 2^256 possible combinations. That is 115 quattuorvigintillion different circles! In practice though, a 50-pixel wide circle and a 50.001-pixel wide circle look the same and most of those circles won’t even fall on your canvas at all.

When creating interfaces for procedural systems, focus on exposing parameters that allow for interesting variation.

The Blue Square

Imagine a program that draws squares like the one below. What parameters might such a program accept?

Parametric Design

Parametric Design is a design approach where designs are defined as systems that produce output that can be customized by adjusting parameters. For example, a parametric design for a bicycle might accept a parameter for the rider’s height and provide a customized frame to suit.

A critical aspect of parametric designs is that they represent the design intent, rather than just the design product. This allows parametric designs to adjust to fit provided parameters and create new design products as needed.

We often think of parameters as inputs, but the parameters exposed in parametric design can also be thought of as desired traits of the output.

Imagine a machine that makes a snowman. The machine might take parameters for how large the bottom, middle, and top snowball should be. This interface would afford a good deal of flexibility, but might also lead to poorly proportioned or even infeasible snowmen. Instead, the machine could be designed to take a single parameter representing the desired height of the snowman, and internally calculate the sizes of each snowball according to relationships determined by the designer rather than the user.

Benefits of Parameterization

You explore the range of a procedural generation system by changing the values of its parameters and seeing what happens. In simple sketches, you might tweak parameters directly, by changing hard-coded values directly in the source.

It is almost always worth taking time to identify useful parameters in your code, consider their possible values, and expose them in a way that encourages exploration. Doing so will lead to better user experiences, better code, and better results.

Better User Experience

Exploring the parameter space of a system by tweaking hard-coded values doesn’t work very well. Tweaking hard-coded values is slow—the project has to be rebuilt and re-run after each change—which discourages exploration. Also, a slow feedback cycle makes it harder to understand the effects of each change. Tweaking hard-coded values in the code is also difficult and error-prone. Which values should you change for particular effects? Do you need to change the value in multiple places? Will changing a particular value just break things?

Exposing key values in your program as parameters makes them easier to document, understand, and use. These benefits of a good interface usually far outweigh the time required to implement it.

Better Code

Procedural generation code often grows organically and iteratively: tweak some code, run it to see what it builds, get inspired, and then tweak again. Iterative growth leads to code that is increasingly disorganized, hard to read, and hard to change. Exposing parameters helps to organize the code by separating configuration and implementation.

Exposing parameters doesn’t necessarily require creating a GUI for them. Early versions of a program often contain a lot of magic numbers. Simply changing these magic numbers into named constants helps make the code easier to read and easier to reason. Organizing your code into well-factored functions with carefully chosen parameters helps even more. Thinking of your program as a collection of components—each with its own parameter-driven interface—will generally lead to better-organized, more maintainable code.

Better Results

On small projects—projects that you don’t plan on sharing—it is tempting to skip the time needed to clean up code, factor out parameters, and create a better UI. This is often a false economy. These efforts are usually quickly repaid.

When you can explore the parameter space of your procedural systems more quickly, you can explore it more thoroughly. You will find more interesting possibilities, ideas, and aesthetics to explore further.

Parameters & Interface Design

Interfaces

When thinking about software we often define the interface as the part of the application that is visible to and manipulated by the user. I think it is better to consider an interface as a common boundary, or overlap, between two systems. Interfaces are shaped by the qualities of both systems.

Two of the most important types of interfaces of software systems are user interfaces (UIs) and application programming interfaces (APIs).

-

The UI is the part of a software system that a person uses to control it. The UI accepts user input and provides feedback. It overlaps with the user and is designed around the capabilities and nature of both the software and the user. The UI is the primary interface in most applications.

-

The API is the part of a software system that is used by programmers to connect it with other software systems. A well-designed API considers both the software system itself and how other software systems will want to use it. The API is the primary interface in most libraries.

It is common for a piece of software to have both a UI and an API. For example, Twitter provides a user interface for making and reading tweets and an API for integrating Twitter into existing systems.

Exposing Parameters

Exposing parameters allows artists and designers to create systems that can be controlled by others—and themselves—more easily. Choosing which parameters to expose is a core concern of software interface design. When choosing, consider the following:

- Which parameters should be exposed?

- Which parameters are required, and which are optional?

- Which values should be accepted for each parameter?

I sometimes find it helpful to consider whether my parameters should be process-oriented or goal-oriented. By process-oriented, I mean parameters that control what the procedure does. By goal-oriented, I mean parameters that control what the procedure achieves. This isn’t a concrete difference and programming languages don’t make a distinction between these things. This is just a way of thinking about parameters and their purpose that can be helpful when designing interfaces. If you take an internal, hard-coded value of a function and turn it into a parameter, it will probably be a process-oriented parameter almost by definition. It often takes a little more effort, and some additions to the code, to introduce a goal-oriented parameter because the code needs to figure out how to reach the goal.

Balance

| Exposing more… | Exposing less… |

|---|---|

| gives your user more control. | gives you more control. |

| makes your interface harder to understand. | makes your interface easier to understand. |

| allows your users to do more good things. | prevents your users from doing bad things. |

Presenting Your Interface

Once you have decided what to expose via your interface, you must consider how to communicate your interface options to your users:

- What will you name each parameter?

- What UI controls will you use for each parameter?

- How will you group and order the UI controls?

- How will you explain the purpose of each parameter?

Feedback

Feedback shows users the impact their actions have on the system. Without feedback, systems are very hard to learn and use. With clear and responsive feedback, even systems that are difficult to describe can often be intuitively understood.

In simple cases, showing users the end result of their choices after each change may be enough. In more complex situations, it is often helpful to provide intermediate feedback. Many procedural systems are too complex to provide real-time feedback. For systems that take a long time to calculate, providing immediate confirmation of user input is important. Sometimes it can be very helpful to provide a low-quality, but quick, preview as well.

Keep Your User In Mind

The way that you think about your software system is often very different from the way your users think about it.

- Who will be using your software?

- Why will they be using it? What will they be trying to do?

- Do they understand how your software works under the hood? Should they?

When designing, step back and consider the relationship between your project and your user.

Fictional Machines

Practice designing user interfaces without real-world constraints.

Begin by thinking about your machine and your user. What does your machine do? What does your user need?

- Choose a machine from the list below. Spend 5 minutes thinking about the full range of options your machine might be able to support.

- Choose a user from the list below. Spend 5 minutes considering the relationship between your machine and your user.

Think about how your user will control your machine. What options would the user want control of? What would the user want automated?

- Imagine one method-oriented parameter to expose to your user.

- Imagine one goal-oriented parameter to expose to your user.

- Imagine one parameter you will not expose to your user.

- For each parameter carefully choose a name, data type, and possible values if applicable.

Machine Types

- A self-driving car

- Planet terraformer

- Grocery-shopping bot

- Song Composer

- Genetic pet builder

- Love potion mixer

Users

- A daily user

- A one-time user

- A child

- An enthusiast

- Another machine

- A technophobe

Study Examples

Globals as Interfaces

A quick-and-dirty way to make your comp form sketches “tweakable” is to use global constants for your parameters and group them at the top of the script. This is very easy to set up and works particularly well for small one-off sketches. However, this approach slows down exploration because you still need to re-run your sketch after each change.

- Choose clear variable names that explain the purpose of each parameter.

- Use comments to explain the parameter in more detail, document legal value ranges, and suggest good values.

- Keep in mind that global variables are evil. Use constants instead of variables, if your language supports them. If your language doesn’t support true constants, use a naming convention, such as all caps, to indicate that a value shouldn’t be changed.

Take a moment to explore the parameter space of the sketch above by tweaking the globals. What happens if you set them both to 100?

Method-oriented vs Goal-oriented

These next two examples both have a function named stipleRect() that fills a rectangular region with randomly placed dots. The first four parameters of each implementation are the same: left top width and height. The fifth parameter is different. In the method-oriented example, the fifth parameter controls how many dots to draw directly. In the goal-oriented example, the fifth parameter controls how densely the dots should be placed, and the function internally calculates how many dots it needs to draw to achieve that goal.

Stipple Rect (Method-oriented)

Stipple Rect (Goal-oriented)

HTML Interfaces

The p5 DOM functions provide functions that allow you to create HTML elements and use them as interface controls. This is a little more complicated to set up but still pretty quick. GUI interfaces are usually better than global variables if you want anyone else to adjust your parameters. You should consider this approach even for projects only you will use; it allows you to explore your parameter space without having to reload and restart your sketch.

Tweakpane

Tweakpane is a JavaScript library that lets you quickly set up and display an interactive pane for adjusting parameters.

Coding Challenges

Explore the study examples above by completing the following challenges.

Modify the Globals as an Interface Example

- Make each square a different randomly-chosen size.

• - Add a white stroke to the squares.

• - Add a global variable parameter to control the width of the stroke.

•• - Add global variable parameters to control the minimum and maximum size of the squares.

•• - Draw the squares in two sizes: small and large. Randomly decide which of the two sizes the square will be.

••• - Add parameters to control the small size, large size, and percentage chance of drawing a large or small square.

•••

Modify the Tweakpane Example

- Add a color picker to control the background color of the sketch.

•• - Instead of drawing the square, draw a “target” of concentric rings that alternate between white and the chosen color. Draw more rings to make a bigger target.

•••

Keep Sketching!

Sketch

Continue experimenting with procedurally-generated images. Focus on exposing parameters and exploring the parametric potential of your sketches. You can mix random and parametric elements, but consider doing a couple of sketches that are not random at all.

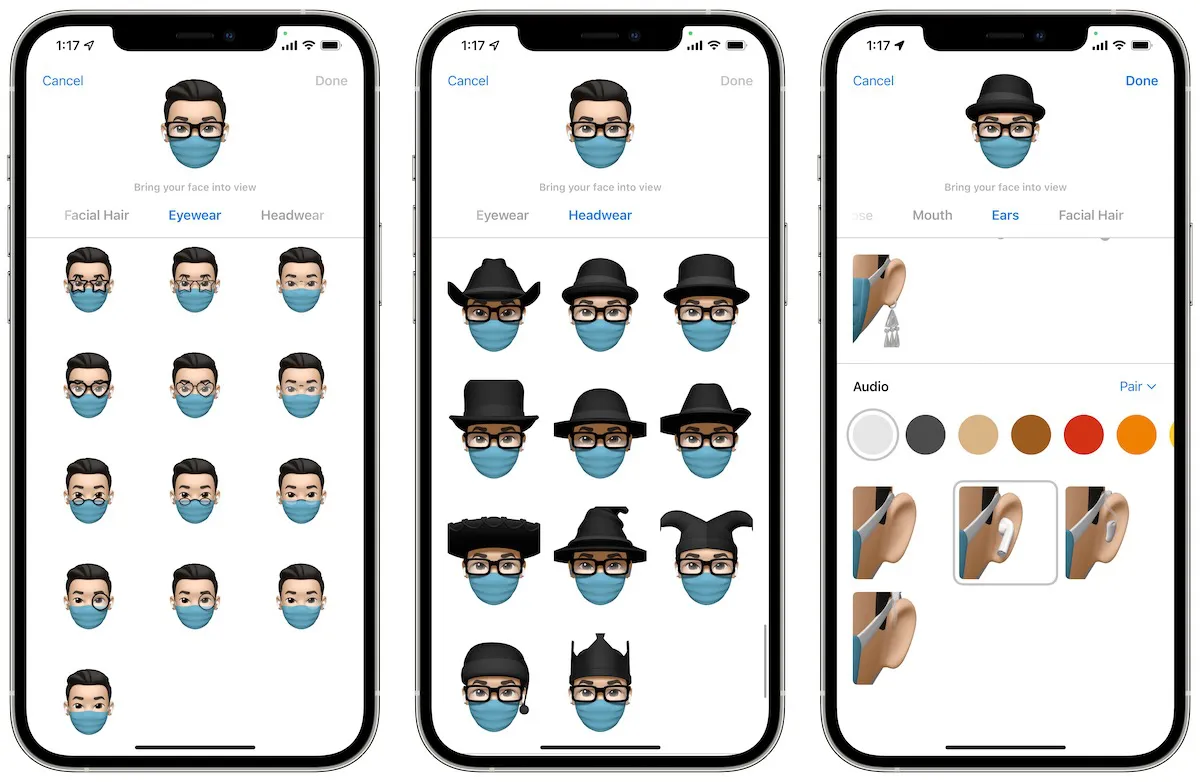

Challenge: Face Generator

Build a face-generating tool. This tool will create an image of a face that can be adjusted by the user with sliders and other inputs.

- Don’t use the built-in shape drawing commands like

rect()andellipse(). Build your face from manually-created illustrations or photographic images. - Make your resulting images look as seamless and cohesive as possible.

- Inputs can range from straightforward (eye color, nose size) to complex (anger, lighting).

Pair Challenge: Code Swap

- Create a computationally generated image.

- Pass the code—not the image—to your partner.

- Extend the code in any way you wish.

Explore

A History of Parametric Essay A history of parametricism and parametric architecture, beginning before the invention of the computer.

Safavid Surfaces and Parametricism Essay An article describing how “digital fabrication and parametric design tools have brought about a contemporary resurgence of surface articulation”.

Variable Fonts Collection A compilation of OpenType variable fonts which offer parametric control over weight, contrast, and other variables.

Engare Puzzle Game A game about motion and geometry that draws on the mathematical principles of Islamic pattern design.

.jpg?1384455904)